Vivienne Tam Spring 1997 Turned Fashion Into a Religious Experience

[ad_1]

Welcome to Forgotten Fashion Shows, a deep dive into some of the more niche runway presentations in fashion history—which still have an impact to this day. In this new series, writer Kristen Bateman interviews the designers and people who made these productions happen, revealing what made each one so special.

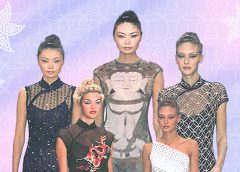

Evocative, almost shocking imagery of Buddha and Kuan Yin—the Chinese Bodhisattva and goddess of compassion, mercy and kindness—plastered onto clothing worn by the Iberian supermodel Irina Pantaeva, Frankie Rayder, and Alice Dodd. The tune “Face of Love” by Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan from the movie Dead Man Walking. Such an eclectic combination could only be found at a Vivienne Tam runway show from the mid ’90s.

The designer’s spring 1997 presentation was a muted but impactful show that featured religious iconography in an entirely new format. Digital artwork inspired by Chinese temples served as the backdrop for the runway. Kuan Yin floated on mesh dresses and tank tops, calling to the temples Tam visited her entire life growing up in Hong Kong. “It was one of my favorite collections,” Tam tells W. “You know, I didn’t realize when I did the Buddha collection that it would be loved by so many people. I guess the message was really good.”

“I used to go to the temple all the time with my mother and I saw Kuan Yin, the goddess of mercy with such a beautiful face,” Tam adds of her inspiration behind the collection. “I thought, I would love to be able to put it on the clothes so that more and more people know about her face. Instead of going to the temple, they could just look at the person who wears each piece.”

By the time this show took place in the late ’90s, Tam was pushing the boundaries of fashion in a way many of her contemporaries weren’t. She often mixed her clothing with political imagery like pictures of Mao Zedong— shocking her audience and captivating her biggest fans in the process. Tam made her entrance into the industry by launching her label East Wind Code in 1982, the name directly linked to “good luck and prosperity” in Chinese. During that period of time, Tam moved to New York from Hong Kong and created clothing that merged Western trends with Eastern imagery inspired by her upbringing. In 1993, she changed the name of her brand to Vivienne Tam and hosted her first runway show. Just two years later, she gained the industry’s—and the world’s—attention for her aforementioned spring 1995 Mao Zedong collection, created in collaboration with the artist Zhang Hongtu. In it, Mao Zedong was pictured wearing pigtails and looking cross-eyed with a bee perched on the tip of his nose; these images were screen printed onto column dresses, T-shirts, and jackets. Tam’s star power was well on the rise by 1997, and her legacy remains imprinted upon fashion today.

“I love my ’90s collections,” Tam says. “I think the world—and, at that time, America—really opened up. The whole world was blooming, and you could really feel freedom of expression. There were less restrictions than there are today.”

But Tam’s spring 1997 collection remains significant beyond the fact that it was a personal favorite of the designer’s. In ’97, the brand opened its New York store in SoHo, followed by locations in Los Angeles and Tokyo. Tam found fans in the likes of Julia Roberts and Madonna, and Beyoncé was photographed wearing one of the famous Kuan Yin T-shirts. The designer was nominated for the CFDA Perry Ellis Award for New Fashion Talent that same year; the signature Buddha/Kuan Yin printed mesh dress in this collection was also archived by the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In 2015, the look was included in the Costume Institute’s most-attended fashion exhibit in history, “China: Through The Looking Glass.” (It was also featured in the acclaimed documentary “The First Monday in May,” which chronicled that year’s Met Gala.) Today, pieces from spring 1997 are fetching thousands of dollars on resale sites, and the TikTok community is rediscovering the brand and falling hard for its unique aesthetic, as well as its intellectual play on cultural topics.

While creating the Mao Zedong line, the designer had a hard time finding a manufacturer to create the pieces. In some countries, the clothing was banned—a small protest even occurred in Hong Kong over the collection. Today, religious figures can be found all over fashion. But back then, Tam had broken major ground. “Thailand told me you cannot put Buddha on shoes,” she says with a laugh.

The spring 1997 collection also included a range of pieces featuring Tam’s signature earth tones with simple silhouettes. In the show notes distributed to press at the time, the designer wrote, “I want everyone to be able to wear my things. They’re not expensive, and anyone can match the pieces with others, or with their own things, and their own style and personality come through. To me, this is more interesting than simply dictating how I think people should look.”

Another point worth noting: the high-end craftsmanship seen in a ready-to-wear show—a rarity for that era of fashion, especially in the New York scene. There were embroidered, sparkling cheongsams; brocade trousers; bamboo-painted slip dresses; heavy, beaded camisoles; and skirts covered in gilded goldfish, as well as snakeskin bustiers. Golden Buddha dresses were cut asymmetrically and wrap tops could be found rendered in the sheerest whisper of lace. “I don’t think these pieces could be made today, “ she says. “They’re too complicated and nobody wants to do it.”

At the time, Tam was living in the West Village and recalls being very into reading spiritual books and doing yoga. “Each collection, I want to say something,” says Tam. “Basically, the Buddha face was kept in a temple, but every time I went there, I felt so connected with her face and felt so much calm and peace. I figure, why not let me share it with more people, show them the history and who she is?” Today, the image projected across a dress has just as much of a powerful presence.

[ad_2]

Source link