Dioseve wants to help infertile people with tech that grows egg cells – TechCrunch

[ad_1]

Based in Japan, biotech startup Dioseve’s ambitious goal is to grow human oocytes, or eggs, from other tissue. Its aim is to help people struggling with infertility, and it recently raised $3 million led by ANRI, with participation from Coral Capital.

Dioseve’s mission might sound like it comes out of science fiction, but it’s based on a scientific technique called induced pluripotent cells stem (iPS) cells, which was first developed in 2006.

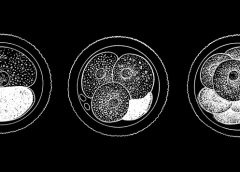

The startup’s scientific advisor, Dr. Nobuhiko Hamazaki, a research specialist at the University of Washington, created Dioseve’s technology, called DIOLs (directly induced oocyte-like cells), which can turn iPS cells into oocytes en masse. DIOLs is currently in trials and has been published in scientific journal Nature.

The new funding will enable Dioseve to hire more people and accelerate its research and development. It aims to establish proof of concept by having mice give birth with DIOLs produced oocytes, and recently established a new lab in Tokyo and hired an iPS specialist.

As Dr. Hamazaki explains, induced pluripotent stem cells can be used to grow all of the cells in the body. For example, other researchers are finding ways to use iPS to grow organs outside of the body, induce beta cells in the pancreas in an attempt to cure diabetes and generate neural stem cells to cure spinal injuries. iPS cells can be made from tissue like muscle or blood cells.

DIOLs first makes primordial germ cells, the source of sperm and oocytes. It differentiates between them to find oogonia, or the precursor of oocytes and then introduces genes into the iPS cells. This means that people who are dealing with infertility can potentially use DIOLs to have offspring with their own genetic material.

Dr. Hamazaki said that in the case of mice, it usually takes 30 days to get oocytes, and that with human oocytes, it can take up to six months.

Dioseve’s CEO is Kazuma Kishida, who became interested in biotechnology when he was diagnosed with hepatitis C as a teenager. At that time, the available treatment had heavy side effects and a low response rate, so his doctor told him to wait a few years, since a new drug was being developed in the United States. After three years, Kishida got the treatment, curing his hepatitis C. “That drug really changed and contributed to the world,” he said. “I wanted to do something that could change the world like the new drug did.”

Kishida said Dioseve has been giving a lot of thought to the safety and ethics of DIOLs by having conversations with potential patients and science and medical ethics specialists. Right now, issues it is monitoring include the inheritance effect of the technology—can it not only produce healthy babies, but also avoid health issues in subsequent generations?

“We are really serious about ethics. We need to be very careful because this technology can be applied to the process of making a child,” said Dr. Hamazaki, adding “we need to have a deep conversation with society to get a consensus if this is applicable, and the range we can apply this technology.”

Dioseve isn’t the only biotech startup researching ways to grow human oocytes. Others include Ivy Natal and Conception, both based in San Francisco, which are also developing ways to grow eggs from other cells. Dioseve says its competitive edge is its research progress and practicality.

[ad_2]

Source link