Science Fiction: Time Travel Can Work — If Clear Rules Are Chosen

[ad_1]

Time travel is such a familiar story element (trope) in science fiction that it has a name, the Time Travel Trope. It annoys me — though much less than others — is the Time Travel trope. These story elements can drive classics such as The Terminator (1984) and utter garbage like A Sound of Thunder. (2005).

Establishing the rules for time travel

The main reason is that there are many different types of Time Travel stories as well as a variety of rules to go with them. The rules depend on which approach to time travel the writer chooses to take. The writer can chooses to go with the idea that the present and future are fixed, and regardless of what the protagonist does, the flow of events will remain the same. Or the writer can go with the Butterfly Effect rule, according to which the tiniest change can drastically alter the present and future.

Avengers: Endgame (2019) dealt with the problem of the Butterfly Effect in a way I liked: Just because someone changes an event in the past that doesn’t automatically change the future because the characters understanding of events are still determined by their initial timeline. Allow me to provide an example:

Say Ironman goes into the past to kill baby Thanos because Thanos used the Stones to wipe out half the population of the universe. If Ironman succeeds and Thanos is no longer able to use the stones, then how does Ironman know to go into the past to kill Thanos in the first place? Changing the past in such a drastic way creates a time loop which collapses in on itself. So, if someone steps on a butterfly in the past and drastically alters the future, then that person could potentially not return to the past to step on the butterfly.

What would happen instead is that reality would go on unaltered because Ironman’s own past is fixed, no matter what he does. I thought the Hulk’s explanation of this in Endgame was pretty clever and made sense. And it was very validating to me personally because I’ve always hated the Butterfly Effect rule.

I despise this rule because there is no way to establish the stakes. The writer is forced to pick and choose which rules have an effect on the future and which ones don’t. Unless the writer chooses to keep the rules as ambiguous as possible — which would require abandoning the Butterfly Effect anyway and then there is no way to establish the stakes within the story. The character must sneak around, but unless no one sees him, he or she is bound to change something, and that just creates confusion.

Some sitcoms have poked fun at this notion. The Fairly OddParents! (2021) even had an episode where Timmy, the central character (protagonist), thinks he’s returned everything back to normal by the end of the episode only to find out his name is now “Internet” because he had a chance encounter with Bill Gates, who decided to call the Internet “Timmy” instead.

Overall, I’d say the Butterfly Effect creates more confusion than anything else and does nothing to establish the stakes within a story.

Another pet peeve of mine is time travels stories set in the future. As with the Multiverse trope, the viewer is left waiting for the rest of the story to happen. The main characters are seldom in any perceived danger in these episodes because — although, most of the time, the writer doesn’t seem to realize this — the viewer expects them to return to the present before the story can end. Unless there is a large cast, how can the viewer return imaginatively to the story present if the protagonist dies? This intuitive audience understanding of storytelling deflates most of the tension. Thus the value is the novelty of the situation and nothing else.

How time travel stories can make sense psychologically

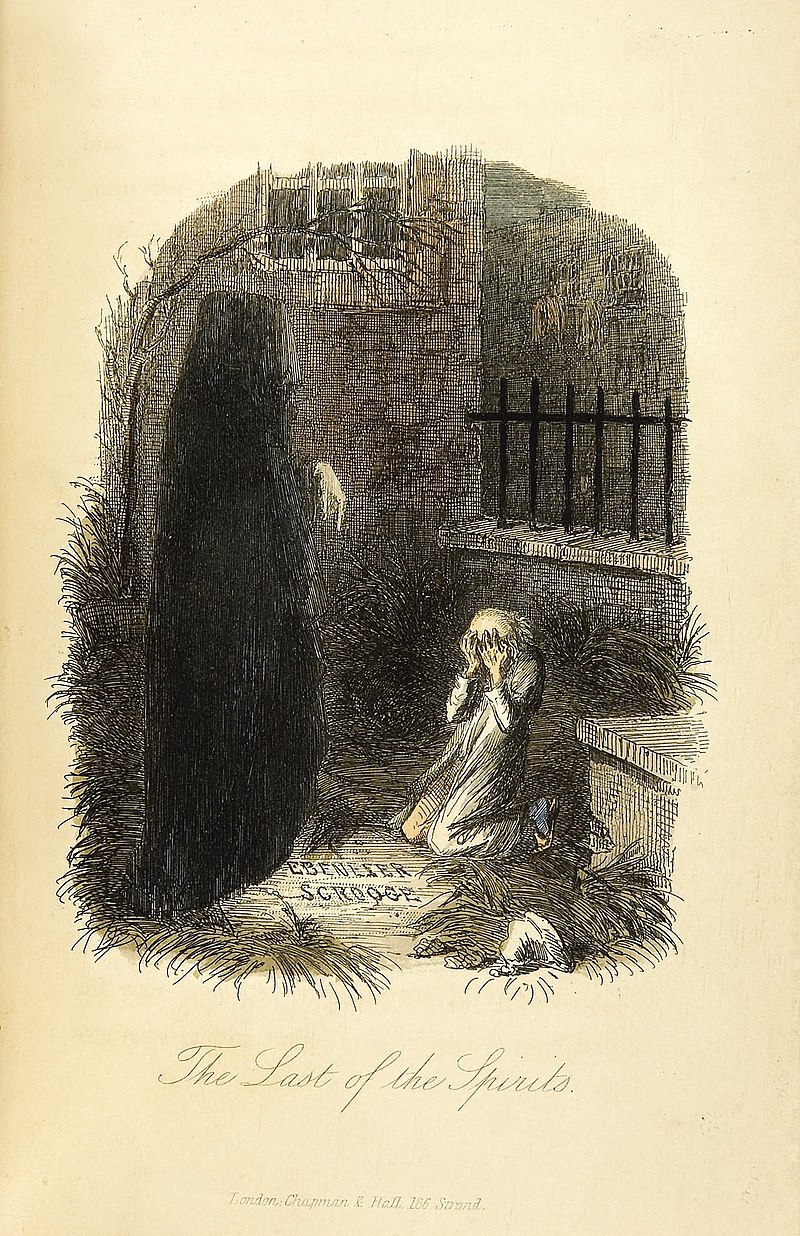

This trope can work as a form of social commentary as in H. G. Wells’s The Time Machine (1895) or as a character arc. It can serve as a warning to people or to the character to change their ways to avoid a horrible fate, as in Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol (1843). But even in this kind of situation, the writer can’t stay in the future for very long. Once the point is made, it’s time to go home.

John Leech, 1843, Public Domain

Now, there are lots of interesting ways to write a time travel story. I think the key to telling them right is to set them in the present and send a character from the past or the future into the modern day. In this way, whatever stakes are established by the story are bound to affect the present, making the protagonist and the audience more likely to care what happens. This also makes it easier to keep the rules of time travel somewhat ambiguous. It can also add a bit of mystery to the story as well as give the writer some flexibility when establishing whatever few rules to time travel he might still need.

The Terminator does an excellent job of this. Keeping things roughly in the present day, and keeping the rules of time travel to a minimum allows the Terminator to become something more than just another killer robot. He turns into an ethereal threat, something akin to a monster — which is why the movie spans both sci-fi and horror. This also allows the movie to go into the question of whether or not fate is set or the future can be changed. Avoiding stringent commitment to rules like the Butterfly Effect, the movie can avoid the need for firm answers, allowing viewers to ask and answer the question themselves.

There are stories that straddle the fence in this regard. Dr. Who has struck a nice balance between the full-blown Butterfly Effect and keeping time travel in a fixed loop. That’s because one character in the series, the Doctor, knows all the rules and his means of transport, the Tardis, is something of a wild card. Using this approach, the characters can make minor changes but if something has happened on screen or is a significant historical event, they cannot change it without dire consequences.

But it’s important to remember that Dr. Who — while it has plenty of dramatic moments — is known for its quirky and unique style. And this brings me to my next point.

How well time travel works depends on the genre and on the stakes

The potential pitfalls of time travel as a story element depend very much on the genre the author has chosen. In comedy, time travel can work rather well because the stakes are low. The fun is mostly situational, and it’s interesting to see, for example, well-beloved characters interacting with historical figures. There is little threat of danger and the stakes established in the story are not taken all that seriously.

Time travel presents challenges when the writer wants the viewer to feel a sense of dread for a character. The tension the audience feels depends on the stakes established earlier and on what needs to happen for a satisfying ending. If the viewer knows that we will all be back in the present again before the story is over, there is no point in putting the protagonist in danger. Unless, of course, the writer really means to kill the protagonist — in order to do that, the writer must build in another way to close the loop of the story. That means making the point of the story about something more than the survival of the protagonist. Perhaps the story points to a moral precept or to the rise of another character who has been hinted as earlier in the story as a person of great significance. Otherwise, the audience will feel cheated.

Next: And now, the trope I hate the most, The Liar Revealed. Permit me to explain why next Saturday.

Here’s my discussion of the science fiction Multiverse Trope: Madness: Why sci-fi multiverse stories often feel boring. In a multiverse, every plot development, however implausible, is permitted because we know it won’t affect our return to the expected climax. Every scene in the multiverse feels like waiting. The viewer will literally be waiting for the rest of the movie to happen while inside the multiverse.

[ad_2]

Source link